Joseph Bazalgette was a civil engineer. In 1852 he was appointed assistant commissioner to the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers. Cholera had struck the capital and ‘The Great Stink’ almost brought Parliament and the city itself to a standstill. Bazalgette’s solution, a network of gravity-fed sewers and steam pumping stations, is recognised as one of the triumphs of modern civil engineering. It established Bazalgette as an invisible architect – designing systems beneath the surface that enabled the fancy stuff to carry on above ground.

Around the same time, another engineer and inventor, Bennet Woodcroft, was creating something equally as spectacular ‘underground’ – the UK’s first patent system. However, Woodcroft’s creation is nowhere near as recognised or remembered as widely as Bazalgette’s, making him one of Victorian Britain’s intangible engineers.

Bennet Woodcroft died on the 7 February 1879. It is likely that he would have wanted to have been remembered as an engineer. He was, after all, Professor of Machinery at University College, London. Failing that, an inventor would seem to be the obvious default position. The most prominent of Woodcroft’s inventions was the variable pitch propeller, which he patented in 1832 and was used in Brunel’s’ SS Great Britain.

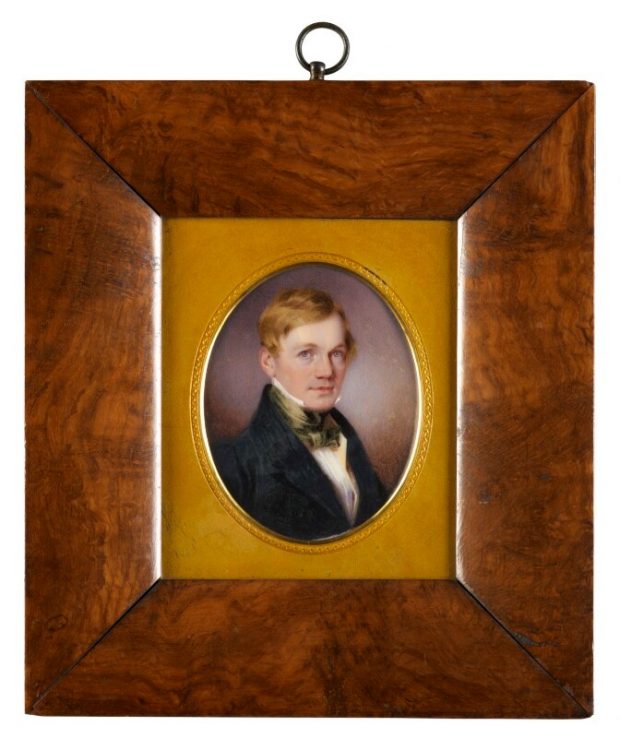

But Woodcroft has been forgotten. Frequent travellers from London to the Intellectual Property Office in Newport will know that Isambard Kingdom Brunel welcomes passengers on to the Great Western Railway. The only effigy of Woodcroft is in the leafy seclusion of London’s Staple Inn, where he appears under a window, looking disconcertingly unreal.

The Patent Office

In the same year Bazalgette took up his position in the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers, the Patent Office opened. Bennet Woodcroft, as ‘Superintendent of Specifications’, began a quarter of century’s work, creating the UK patent system. He was described by a Select Committee (who were looking into the mess that characterised the patents system at the time), as the only person with a complete list of patents in the country. Just like the river Thames, the realm of intellectual property was in desperate need of some pipework.

Woodcroft was a visionary administrator who transformed the organisation of a highly technical field, where specialist factions could not agree on the best way forward. He was a master of information dissemination. Woodcroft turned intellectual property into a system that placed technology, information, objectivity and transparency in the hands of those who most need it - the people.

Perhaps Woodcroft’s roots in Lancashire gave him an instinctive understanding that libraries and journals carrying patent specifications should be spread throughout the UK. The abridged books of patents produced by The Patent Office and arranged by subject matter, were known as ‘Bennet Woodcroft’ volumes.

Iconic institutions

But Woodcroft’s brilliance wasn’t confined to the realm of administration. As Assistant to the Commissioner of Patents, with support from Prince Albert, he created The Patent Office Library and The Patent Office Museum. These two extraordinary institutions transformed the Patent Office from a necessary institution into an inspirational one. The Library, which developed from Woodcroft’s own patent indexes from 1617–1852, grew into what was reputed to be one of the best technical libraries in the country before it became part of the British Library.

The Patent Office Museum was a magical place, designed to inspire students, the curious, the young and the old. Once again, Bennet provided the means to set it up. His own collection of models formed the basis of the museum, but his imagination knew no boundaries. The museum grew to include real inventions, not facsimiles. These included Puffing Billie, the world’s oldest surviving railway steam engine and Stephenson’s ‘Rocket’. In 1857 the museum, which was free to enter on Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, attracted around 1500 people a week and, in 1884 became a formative part of the of present day Science Museum.

Bennet died in 1879. For him, invention, creativity and the creation of the new was not an activity reserved for a privileged class or a particular region. Nor was it a form of activity like any other. Bennet’s genius lay in his ability to transform an idea about the structure of collective creativity into a system and an icon, The Patent Office.

To keep in touch, sign up to email updates from this blog, or follow us on Twitter.

6 comments

Comment by Prof Roger Cullis BSc DMS PhD CEng CPhys FinstP FIET CPA posted on

I am Professor of Intellectual Property Law and Technology at the Centre for Commercial Law Studies, Queen Mary University of London. Bennet Woodcroft published his iconic Alphabetic Index of Patentees of Inventions in 1854 which laid the foundation for the modern patent system. He died in 1979, which means that his Index has been out of copyright for nearly 100 years. I am concerned that the only way of extracting useful information on Industrial Revolution technology from it is by thumbing through the 647 pages of the printed version published in 1969 (copyright only in the typescript). I am currently preparing an open source digital version to be accessible online via the Espacenet World Patent Database but, based on my prior experience of creating a database of the 9,000 patents assigned to the National Research Development Corporation, I anticipate that creating a Microsoft Excel file of the 16,000 Industrial Revolution patents will take around four years, maybe longer because I am currently establishing a company to counter climate change by using Industrial Revolution technology and infrastructure.

Comment by Julie Barrett (CPA, EPA) posted on

Hi Paula, I agree. It is a very interesting article (I have now had time to read it!), and reminds me of my early days in the profession when you could go up to the Patent Office in London and browse through physical copies and card indexes of patents, inventors/applicants and much more. Although there is a myriad of advantages to our increasingly sophisticated methods of storing and retrieving such information today, I can't help feeling that we have also lost something inspirational and magical from discarding those tangible symbols of intangible (IP) rights. Thank you for an article that brings this heritage to consciousness again. Julie

Comment by Tony Buckley posted on

What an excellent and interesting article. Thank you. As an intellectual property specialist who started his career as a chartered civil engineer in the water industry I see no problem associating invention and sewers. There has been considerable innovation in sewerage and drainage in the last 30 years. However, I did hesitate over the description of Bazalgette as an "invisible architect". Perhaps his visible works, such as Crossness and Abbey Mills PSs, were architectural but the underground works and embankment were mostly definitely the works of a a civil engineer.

Comment by Paula Davy posted on

Hi Tony. Glad you enjoyed reading the blog. It was certainly a history lesson for me, which I also found very fascinating. Many thanks, Paula

Comment by Julie Barrett posted on

Initially incredulous at the UK IPO using sewerage as a metaphor for inventions. (This is more obvious in the email sent advertisong this blogpost.) Whatever next! May read the article when I've recovered from the surprise!

Comment by Paula Davy posted on

Hi Julie.

Thanks for the feedback. I hope you do read the blog - I personally found it really interesting.

Many thanks

Paula